A brief look

- Since 2009, $16 billion has been invested in the plant-based protein industry with more than $1 billion invested in plant-based meat substitutes alone between 2017 and 2018.

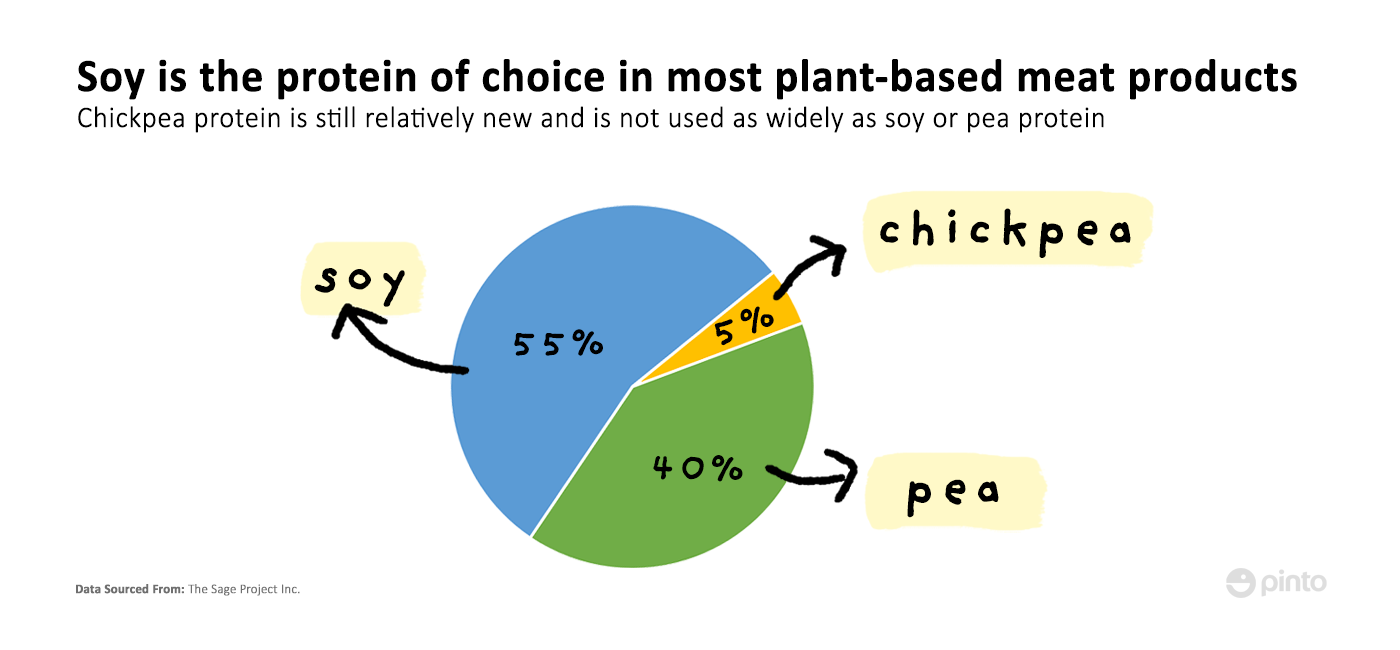

- Soy, pea, and chickpea protein are jockeying for dominance in the industry.

- Chickpea protein remains the least popular plant protein among the three despite its multifaceted functionality and neutral taste profile.

- Although soy protein is cheaper than pea protein, many manufacturers have turned toward pea protein as anti-GMO sentiment continues to grow among consumers.

Dive deeper

Look at the ingredients label of any of the plant-based meat products on the market and you will probably find pea protein isolate, soy protein concentrate, or organic chickpea protein among the ingredients. These plant proteins are typically used as the main ingredient of plant-based meats because they have an amino acid profile that is similar to that of animal-based protein. Manufacturers may choose to include one or a combination of the proteins in their formulation. In a comparison of most of the plant-based meat products found on the shelves of American supermarkets, we found that among the three legume-based plant proteins, soy was the most prevalent, followed by pea and chickpea.

So why these three proteins and not other ones? This is because all three have what is considered a complete or nearly complete protein profile. That means that they either contain all or almost all nine essential amino acids (histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine). Soy is a complete protein however, compared to meat it is particularly low in methionine*, one of the nine essential amino acids. Both chickpea and pea are also deficient in methionine. This is why you also see other plant proteins with higher methionine levels such as potato or rice protein being used in conjunction with them. Since all three proteins have a complete or nearly complete amino acid profile, what drives a company to choose one over the other?

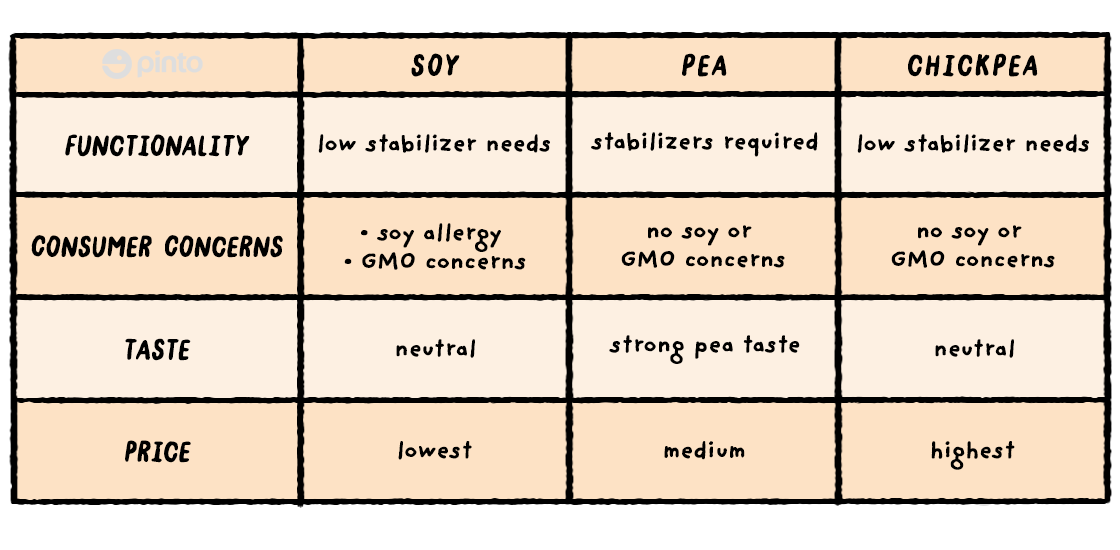

It can be narrowed down to four driving factors: functionality, consumer demand, taste, and price. The table below offers a comparison of the three proteins based on these factors.

This table seems to place pea protein dead last among its plant protein competitors. However, pea protein is actually found in 40% of the products in the Pinto database while chickpea protein—although technically better in three out of the four categories—is only found in 5% of the products. When selecting ingredients, manufacturers must consider a number of important factors, including price, consumer demand, functionality, and taste.

Pea protein is found in 40% of the products in the Pinto database while chickpea protein is only found in 5% of products.

However, each manufacturer may have slightly different situations and priorities to consider. As we delve into the details, you’ll get a better understanding of why pea protein often wins out over chickpea protein despite its shortcomings.

The tricky science behind texture and mouthfeel

Crumbly, chalky, gristly. These were some of the words used to describe plant-based meats in their early days. Making “meat” out of plant protein powder and stabilizers was and still is no easy feat.

So, how exactly are plant protein powders used in plant-based meats? To provide the base for the product, protein powder is mixed with water, forming a solid but malleable mass. At this point, however, the mixture doesn’t have the ability to hold itself together as well as animal-based meat does. Hence, stabilizers and emulsifiers must be added to give it the desired mouthfeel and texture. Through constant tests and trials, plant-based meats have steadily improved in terms of texture and taste. Nevertheless, different plant-based proteins still yield different results when it comes to texture and mouthfeel.

Pea and soy protein isolate are widely used in plant-based meats, either on their own or in combination. Studies show that pea protein isolate has a lower emulsifying capacity and stability than soy protein isolate. This means that pea protein does not bind fats as well as soy protein, which affects the texture of the product. With the help of stabilizers and emulsifiers though, this can be changed. These ingredients help to bind fat to the product, thus giving it a juicy texture that mimics meat. Chickpea protein, on the other hand, wins out over the other two plant-based proteins when it comes to functionality. Innovopro, a producer of chickpea protein, says that emulsifiers such as carrageenans and modified starches can be removed just by adding 2% of chickpea protein.

Since both soy and chickpea protein isolate have a better emulsifying capacity than pea, that also means lower amounts of stabilizers need to be added. Why then would someone choose to use pea protein?

GMO and allergy concerns may threaten soy’s dominance

Almost all soy in the U.S. has been genetically modified to some extent. Some consumers prefer to stay away from GMOs and thus they avoid products that include soy. In addition, soy is also recognized as one of the Big 8 Allergens by the USDA, which means that any soy-containing product is automatically shut out of a portion of the consumer market. This has caused some manufacturers to turn to non-GMO, allergen-free pea protein or chickpea protein.

Yet, even with its multifaceted functionality, chickpea protein is used far less often than pea protein in new products. Why is that? Could flavor play a role?

Improving plant protein taste is a daunting challenge

Taste is particularly important in the realm of plant-based meats. When plant-based meats were a novel product, consumers often complained that the product had an off-flavor, and that it tasted nothing like meat. Now, some plant-based products taste and even bleed like meat.

However, not all plant-based proteins make the process of creating that meaty taste easy. Pea protein, for example, has a pronounced taste of, well, peas. To mask that, more flavoring and salt has to be added to the product, increasing production costs. Soy and chickpea protein, on the other hand, have a more neutral taste. What then would make someone choose pea protein over soy or chickpea? Soy already has the GMO and allergy-related strikes against it, but what about chickpea? The answer is simple. Money.

Global supply issues and new formulations could shake up the market

As it currently stands, soy protein is the cheapest while chickpea is the most expensive. This could also explain why most products in the Pinto database and on the market contain soy protein/flour while chickpea protein is only used in 5% of the products. Chickpea protein is still expensive because, unlike the other two, the demand is not yet high enough to achieve lower production costs. However, chickpea protein makers argue that there is a price trade-off that comes with using chickpea protein. Since the protein is highly functional, more so than soy or pea protein, this means that lesser amounts of stabilizers or emulsifiers are needed to bind or stabilize the product. Moreover, due to its neutral flavor profile, less flavoring is needed to mask the taste of the protein. Thus, both these factors should lower production costs of the product and make the more expensive chickpea protein a viable option.

Even so, manufacturers would probably prefer cheaper raw goods prices over the time and effort required to figure out a specific formulation to make chickpea protein more cost-effective. In addition, soybean prices hit historical lows last year due to the trade war between China and the U.S, as well as a decreased demand for soybean feed caused by the African swine flu epidemic among China’s hog population. This year, due to the coronavirus pandemic, demand for soy has decreased as consumption of meat is down overall. Thus, prices for soy continue to be on the lower end of the spectrum. This makes the procurement of soy much easier for those who produce plant protein powders or isolates.

As long as the product is readily available and prices for it remain low, companies that currently use soy protein might not be motivated to aggressively seek alternatives such as pea or chickpea protein. However, something to keep in mind is that the pandemic has caused some disruption in the logistics and production chain, which could eventually cause prices of soybean protein to increase even if the price of soybean itself is lower.

Soybean prices hit historical lows last year due to the trade war between China and the U.S.

The future for other plant proteins like chickpea protein may hinge on what happens in the market as pea protein becomes increasingly popular. The rise in use of pea protein could eventually put some strain on the pea protein industry, eventually leading to a shortage if producers struggle to keep up with demand. By 2024, the market value of the pea protein industry is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 10.5%. If a shortage happens, it could be the perfect chance for chickpea protein to grab a sizable chunk of the market.

So, which protein will win?

It’s too soon to tell. Soy has the advantage of scale and global dominance. As anti-GMO sentiment grows and food allergies become more common, soy’s other strengths may be sorely tested. Pea protein is the rising star, with only a small flavor problem but a potential shortage looming over it. Chickpea is highly functional and neutral tasting, but the high price continues to hold it back. As new formulations and new production techniques evolve, the battle for top plant-based protein is certain to rage on for years, and perhaps even more intensely than previously thought.

Curiously, the current situation with the pandemic has seen continued rising consumer interest in plant-based meats. In a nine-week period ending May 2nd, there has been a 264% rise in the sales of plant-based meat products. This rate was higher than what was seen in the month of February. In recent months, many fresh meat packing facilities have had to temporarily shut down due to outbreaks of coronavirus within their premises, thus there has been a nationwide shortage of meat, and with that, the prices of meat has risen too. With this, consumers seem to be more likely to try out meat alternatives in this period of time. Due to these recent shifts in the market, it looks like the plant-based meat industry is going nowhere but up and it will be interesting to see which plant-based proteins will reign supreme.

*Links to sources indicating that the plant proteins are low in methionine: soy (1,2), pea, chickpea